The Church of St Michael and All Angels

In writing this section we are indebted to the excellent booklets “The Story of Pirbright Church” (c1930) by John Curtis, and “The Church of Saint Michael and All Angels and The Manor of Pirbright” (2018) by James Grimshaw. The latter booklet is particularly excellent in our view.

Unsurprisingly, there is more far documentary evidence relating to the church than any other building in Pirbright. Likewise, there are far more paintings, drawings and early photographs available. As a result, we have had to be very picky as to what to omit in writing this history. So please accept our apologies if your favourite story/photograph/architectural feature etc has been omitted – it was done in the best interests of preventing the overall project from slowing down too much. Of course you are very welcome to suggest specific items which should be included in the narrative, and we will do our best to include them.

We have divided this page into the following sections:

-

The early days to 1785

-

1785 – 1840

-

1840 - 1900

-

1900 – 1970

-

1970 – date

-

Memorials and plaques

-

The churchyard

-

Incumbents

The early days to 1785

The first evidence of a church in Pirbright is from 1214. In that year, a document about a completely different property was witnessed by one “Jordan, the parson of the Church at Perifricth”. A copy of this document, together with a translation hangs on the west wall of the church.

In fact many people think that there may have been a Saxon chapel on the site well before 1214.After all, there is evidence that a settlement existed at Pirbright in earlier times - Neolithic rings, Bronze Age flints and Iron Age and Roman pottery at The Manor House. However, no evidence of an earlier chapel has been found, and so we keep an open mind on this.

Back to the church which existed in 1214.From various documents, we can deduce the following about this church over the course of the next 550 years:

-

In the 1200s, it fell under the control of Chertsey Abbey, and later Newark Abbey (near Pyrford).

-

It was built on the site of the present church, and constructed largely of Heath Stone (a sandstone found in the area. Today’s church tower is constructed of the same Heath Stone blocks).

-

It had a tower, of which the top portion was made of wood.

-

It had a nave with a north aisle, whose roof and floor were lower than those of the nave. This aisle was separated from the nave by a series of round-headed stone arches.

-

There was a round-headed arch leading to the chancel.

-

The east wall contained a 3-light window which apparently showed a “ducal coronet”. This would suggest that at some stage the Lord of Pirbright Manor was a Duke. The window was replaced in the early 1800s (see below).

-

The nave and chancel had the same floor area as today.

-

It probably had an important role as a staging post for pilgrims on the road from London to Shaftesbury. But later, Canterbury became a more popular pilgrimage destination than Shaftesbury (thanks to Thomas a Becket). Pirbright’s use as a staging post diminished accordingly.

-

It had a peal of 4 medieval bells, which had managed to survive the Reformation in the 1500s. The bells were taken to Henley Park, and one (cast in 1701) survives in Chertsey Abbey Museum (pictured below).

In 1368, the “Chapel of Pyrbright” needed to be solemnly purged (ie purified) after having been “polluted with blood”.This seems to refer to a brawl in which one Simon Serle of “Horsehull” (presumably Horsell) was killed.The King, Edward III, granted a pardon to the “Chaplain of the Hermitage of Brokewode” (John Tylman of Wynchecombe), as the deed was done in self-defence.

In 1617, Thomas Warren(the curate) was convicted of disobedience to the orders of the church.He admitted that (among other things) on one Sabbath, seeing more than half of his parishioners absent, he caused a psalm to be sung, and, with a churchwarden, went to search the ale-houses and bring back to the church such idlers as they found before the psalm ended.Assuming this referred to The White Hart, then it must have been a pretty long psalm...

The churchwardens’ chest which now stands in the chancel dates from the early 1600s.It used to contain the parish records of baptisms, marriages and burials from 1574, among other things.Fortunately for historians, these records have been safely scanned and indexed, and are available online.

In 1642, John Remnant of Cowshott left money for a “new gallery or enlargement of the church there”.This may have been when the first west gallery was built.

During the Interregnum under Oliver Cromwell (1649-1660), the church and village had a puritan priest (Samuel Wickhamof Wickham’s Farm) and a puritan Lord of the Manor intruded on them respectively.After 1660, these 2 people were extruded, and normality resumed.

In 2009, work on the floor of the chancel revealed 2 brick vaults (shown below).They were not opened.We do not know for sure who is buried here.However, George Dawson (curate 1705-1755 – refer below) is one candidate.

A ceiling was inserted in the nave in 1732. Pews were introduced in 1754 (prior to that, the congregation was expected to stand). These pews could be rented to members of the congregation, to pay for renovation work.

The same year (1754), a gallery along part of the west wall was built. This provided more seating, and also had rented seats.

And now to the Rebuilding of the Church. In 1772 it became obvious that the church was deteriorating. And by 1785 the condition became critical. As a result, the inhabitants of Pirbright wrote a petition in 1783 (in Latin) to King George III to raise money to rebuild the church. A copy of this petition (together with an English translation) is framed on the south wall towards the back of the church. The document is long, and difficult to read (and so is the English version). So we have extracted the main points below:

-

“The existing Pirbright Church is a very ancient structure and greatly decayed in the ffoundation walls and roof”. So, the entire structure then.

-

“The parishioners have in the past have laid out several considerable Sums of Money in repairing it”.

-

“Yet the same is become so ruinous and decayed in every part thereof That it cannot be any longer Supported but must be taken down rebuilt and enlarged”.

-

“Thomas Walker and John Butcher (2 able and experienced workmen) have carefully viewed the church and their estimate of taking down, enlarging and rebuilding it upon a Modest Computation amounts to £2,024 5d. Exclusive of the old materials”. We are impressed by the precision of the estimate, but wonder what the 5 pence was for. The total amount is equivalent to £260,000 today.

-

“The inhabitants are not able to raise this sum, being mostly tenants at rack rents and greatly burthened with Poor. They require Charitable Assistance of well-disposed Christians”.

-

“They request permission to Collect Alms Benevolence and Charitable Contributions from House to House throughout England as well as Berwick-Upon-Tweed, and the 3 Welsh counties of fflint, Denbigh and Radnor”. More precision, this time with the geography.

The petition was duly approved.The collection process that followed was interesting:Each parish decided what they could pay.They wrote this sum on the back of their copy of the petition, and returned it to a central authority.When the sums were collected, the money was forwarded (after deduction of expenses) to the parish in need.Pirbright parishioners had contributed to such petitions from other parishes in previous years, so probably had no compunction in using the same system.

In the event, only 25% of the requested sum was raised.Perhaps there had been a high level of “expenses” incurred in the collection process.But the rest of the money was successfully obtained through specific donations.We assume that the recently-arrived Henry Halsey 1, Lord of the Manor from 1784, was a major donor.This would have been an extremely good way for him to make a favourable impression on a new set of tenants.The rebuilding was duly completed by 1785.We give some details of the work at the start of the next section.

1785 - 1840

The 1783-1785 rebuilding work largely related to the nave and tower of the church. The chancel was not affected by this work (though it was subsequently altered in 1812 after Henry Halsey 1’s death – see below). The 1785 rebuilding work involved:

-

The nave was rebuilt in brick (previously it was made of Heath Stone). The footings were made of the local Heath Stone, which had no doubt been part of the original building.

-

The height of the north aisle was raised to the same level as the nave.

-

The columns supporting the roof of the north aisle were replaced by square-cut wooden pillars with a decorated casing.

-

The tower was completely rebuilt in local Heath Stone and embattled.

-

The gallery on the western wall was replaced by a new gallery stretching along the whole length of the wall.

-

2 box pews were installed in the chancel. One on the north wall was for the Halsey family. The other, on the south wall, was for occupants of Pirbright Lodge – Admiral Byron at the time.

-

A massive pulpit (reached by a spiral staircase) was installed at the front of the nave, on the north side.

The small room (actually divided into 2 small rooms) on the south side of the chancel was used as a vestry and storeroom.

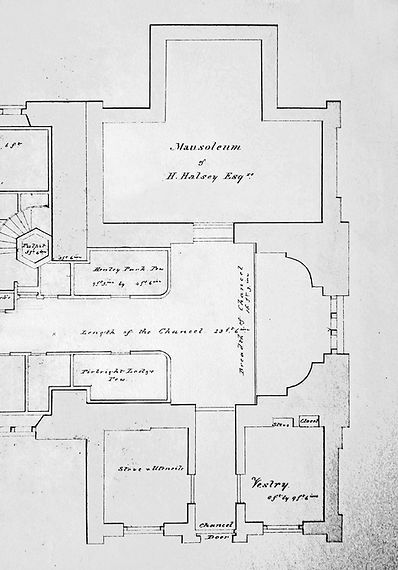

The chancel was reconstructed in 1812 in accordance with Henry Halsey 1’s will (he had died in 1807). This included:

-

The original 3-light window was replaced by a single-light window containing the Halsey and Glover crests. Glover was the maiden name of Mary (Henry’s first wife).

-

The east corners of the chancel were made apsidal (ie shaped like an apse, or curved).

-

A Halsey mortuary was constructed on the north side of the chancel. This was probably part of the arrangement by which Henry made his original donation in 1784-85.

-

A vestry on the south side of the chancel was built.

-

The external wall of the chancel was embattled.

A plan from 1811 showing some of these changes is shown below. An easier to read plan of the whole church is also pictured.

Below are 2 drawings of the church. The one on the left is from 1808. This looks strange to our eyes, because, although the 1785 building works had been completed, the work on the chancel (see paragraph above) had not yet been started. Thus the outside of the chancel looks oddly bare.

The drawing on the right (from 1823) also looks rather odd. Although the chancel now bears its current outline, the battlements give it an unfamiliar, lumpy appearance. Perhaps others felt the same way, as the castellation was removed in 1848.

We are unsure when the first organ was installed. It was described as being of American origin and was replaced in 1895.

In 1819 a local newspaper reported a fire in the church, which was extinguished by water from the nearby stream (one enterprising resident had dammed it). The fire “destroyed the chancel, and slightly damaged the roof”. The drawings of the church soon afterwards show no signs whatsoever of this fire, so we assume that the newspaper was exaggerating its impact somewhat.

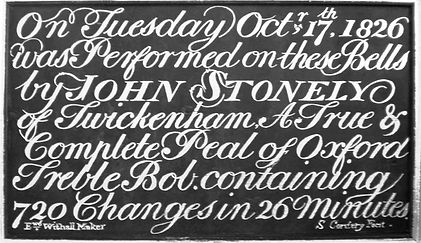

In 1822 Henry Halsey 1 celebrated the marriage of his eldest son and heir, Henry Halsey 2, by donating a peal of 5 bells to the church. A 6th bell was added later. There is some interesting signage in the bell hall from around this time. We have shown below photos of some of it below.

The fine marble font currently in use dates from before 1829. It replaced an octagonal font. In 1902 the marble font was “lent” to St Saviour’s Church, Brookwood. It was not returned until 2011.

To the left is a sketch by Hassall in 1829 looking towards the chancel. The pulpit rather dominates, but we have a good view of the single-light window installed in the east wall in 1812, in accordance the Henry Halsey 1’s will. 18 years later, however, the window was removed (see below). We can also make out that the rear corners of the chancel were apsidal (ie curved). The top of the marble font can just be made out below the pulpit.

Below is an 1835 sketch of the outside of the church by Miss HA Bowles (who was presumably a relative of the curate, Charles Bradshaw Bowles).

1840 - 1900

1848 saw some extensive renovations, largely funded by Henry Halsey 2. They were commissioned by Henry Woodyer, architect, who was a grandson of Henry Halsey 1. The works included:

-

Constructing a north gallery in the nave (removed in 1972). The gallery was used by the choir.

-

Replacing the columns between the nave and the north gallery.

-

The floor of the central aisle of the nave was paved in stone, and the remainder of the nave in wood.

-

Replacing the single-light stained-glass window in the chancel with today’s 3-light window.

-

Removing the exterior castellation of the chancel.

-

Modifying the chancel from its Classical style to a more Gothic style, in particular:

-

Adjusting the shape to its current shape, including removal of the curved corners..

-

Replacing the chancel arch by today’s pointed arch (made of chalk blocks).

-

In 1872 oak choir stalls were placed along the north and south walls of the chancel.

By 1877 the Halsey mortuary chapel had become so full that it had to be closed. (In fact, we think that the last person was laid in the mortuary 28 years earlier in 1849). The remains in the mortuary were buried under the floor and sealed, and the chapel was converted to a vestry. The old vestry on the south side became a side chapel devoted to the Halsey family. Arches were inserted into the north and south walls of the chancel. This would have opened up the front of the church considerably. East-facing windows were built in both of the new rooms, as were fireplaces (which have since been replaced by central heating).

The same year (1877), the old box pews in the nave were replaced by today’s pews.

10 years later, (in 1887) a clock was installed in the church tower to mark Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee. Suggestions for suitable ways to mark the jubilee had been sought from residents earlier in the year, and in the end, a clock was deemed to be the most popular choice.

In 1895 Lord Pirbright donated an organ, which was installed in an opening of the north wall of the chancel. The organ pipes were installed in the nave at the end of the north gallery. The following year (1896), the church bells were refitted and the oak framework replaced. The bells weighed 2½ tons. “The improvement of tone in the tone in the bells is so very manifest”, wrote the Surrey Advertiser. A service was held in 1896 to dedicate the new organ and the recently rehung bells. The front cover of the order of service is shown left.

In 1899, 8 panels of carved oak were discovered in the coal-shed of the school. They had been produced originally by a village carving class. After cleaning they were cut into 16 pieces and formed into a reredos behind the altar.

We have shown below a painting of the church by Ada Long in 1898.

1900 - 1970

In 1905 it was found that the ivy growing up the tower had weakened the structure. A public subscription raised £140 11s (equivalent to £14,500 today) for its repair. This was more than was required to fix the tower, and so the balance was used to build a new door into the west face of the tower. The present wonderful chancel ceiling decoration of 36 panels (some with an IHS motif) was created in 1908.

The entrance porch on the south wall was built in 1911 by John Faggetter, a local builder. His bill, for £80 19s has survived. The new porch replaced an earlier wooden one which had decayed. Inscriptions on the windows confirm that it celebrated the coronation of George V. Bottles containing the Parish newsletter of the time and other documents were buried in the SE and SW corners of the porch. Below we have shown photos of the old porch (on the left) and the new porch, taken by Ada Long in 1911.

In 1914 a collection was raised to repair the “heating apparatus” of the church and the organ.A program of Thanksgiving and Prayers was said afterwards.

In 1922-24 further changes were made to the chancel. The first set of changes, in 1922, was in memory of Francis Owston (curate 1851-1888):

-

A waist-high wooden screen was installed across the chancel arch to separate the chancel from the nave.

-

An eagle lectern was introduced.

In 1924, A rood and crucifix were set across the chancel arch, supported by 2 stone corbels, high on the arch in memory of Arthur Nield (curate 1898-1924).

In 1933, the bells in the tower were retuned, refitted and rehung on “modern ball bearings”. This work cost £225 (equivalent to £13,000 today). We have shown a picture of the inside of the bell tower, left.

In 1950, the old hot water-based heating system was replaced by system whereby hot air was pumped into the building. As we will see later, this had adverse effects on the organ in the chancel. In 1958 the heating system was again replaced by a system of electrically-operated infrared heaters.

In 1957, the 2 entrance doors to the church were replaced, thanks to a bequest from Commander Basil Guy, VC, DSO, RN, Pirbright’s 2nd holder of the Victoria Cross.

The photograph below was taken from the west gallery sometime prior to 1972. It shows some of the 1923-4 changes. It also shows the organ in the north gallery on the left of the picture.

1970 - date

During 1970-72, a team of 69 ladies in the village set up a project to knit 200 kneelers for the church. 93 original designs were used (81 of which were drawn by Joyce Weston, who lived on the Ash Road. The organizer was Beryl Godwin-Austen, who lived in The Manor House and later Tilsey.

Significant changes were made to the church in 1972:

-

The wooden screen, rood screen and lectern were all removed , thus helping to brighten up the area.

-

The arch in the chancel leading to the Halsey chapel on the south side was filled in, and the enclosed room became a Sunday school, and was then later used for storage.

-

For the 3rd time in 22 years, the heating system had to be replaced. This time an oil-fired hot water system was installed, and is still in place today.

-

The north gallery was removed, as it was unsafe due to dry rot in the floor.

-

The worst-affected area of the floor was cemented over.

-

The west gallery was replaced by the current gallery.

-

The organ was transferred from the north gallery to the new west gallery.

In 1975, the altar was moved away from the east wall of the chancel, so that the priest could stand facing the congregation.

In 1992, meeting rooms were added on the north side of the church. In 1993, major work was required to strengthen the floor of the bell chamber and bell supports.

The various changes to the heating systems of the church (refer above), and the fluctuations in temperature which they produced had played havoc with the organ’s inner workings. By 1982 the organ was close to unplayable. By 1999 it was replaced by a new shiny instrument in the west gallery. It was funded largely by an anonymous donor, and cost £84,000.

In 2003, the clock on the tower was modernized with the addition of an electrically-operated winding system.

In 2008 the infilled arch on the south side of the chancel was knocked through again, and the room (previously a Sunday school room) is now used as a Lady Chapel. This too has helped brighten the church.

Post-2009, the railing in front of the altar was removed.

In 2020, during the Covid pandemic, social distancing rules prevented bell-ringing in the usual manner. However, a small group of volunteers worked hard to reinstate the Ellacombe chiming mechanism. This is a system designed near Bristol way back in 1821 to enable a single person to ring all the bells in a tower, unlike traditional methods that require multiple ringers for each bell. The system had been used in Pirbright Church previously, but had fallen into disuse during the 1950s and 1960s. The tone of the chime is slightly different to the norm, but it did allow bell-ringing to take place while obeying the social distancing rules. There are other benefits – for example, it allows a skilled bellringer to play well-known tunes, such as Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star single-handed…

Memorials and plaques

There are several items of interest on the walls of the church. We have listed some of them below (going clockwise round the church, starting at the entrance), together with a reference where further information can be found.

-

Plaques to the fallen in the two World Wars.

-

A copy of the 1783 petition for a rebuilding fund (refer above).

-

A copy of the 1214 document (refer above) mentioning Pirbright church for the first time.

-

A plaque to Henry Morton Stanley, who is buried in the churchyard (see below).

-

A plaque to Ross Lowis Mangles, Pirbright’s first holder of the Victoria Cross.

-

An embroidered panel to mark 800 years since first known date of the church (a report of the unveiling ceremony is shown below).

-

Halsey plaques (near the altar). Refer to the Halsey family page for more details on the individuals.

-

In the Lady Chapel, a plaque and window dedicated to Major William Armstrong. He and his family lived in the Manor House from 1879.

-

A plaque to George Dawson (refer section on Curates below), who was curate 1705-1755. The Latin inscription translates drily as “Contented with his lot, but relying on the hope of a better one”.

-

A plaque to the Cawthorn family, including Mary Cawthorn, who can claim to be Pirbright’s first historian.

-

A plaque to the Stirling family. They lived in Pirbright Lodge after Admiral Byron, but probably made their money by selling textiles to slave traders in the Caribbean.

Memorials and plaques

There are several items of interest on the walls of the church. We have listed some of them below (going clockwise round the church, starting at the entrance), together with a reference where further information can be found.

-

Plaques to the fallen in the two World Wars.

-

A copy of the 1783 petition for a rebuilding fund (refer above).

-

A copy of the 1214 document (refer above) mentioning Pirbright church for the first time.

-

A plaque to Henry Morton Stanley, who is buried in the churchyard (see below).

-

A plaque to Ross Lowis Mangles, Pirbright’s first holder of the Victoria Cross.

-

An embroidered panel to mark 800 years since first known date of the church (a report of the unveiling ceremony is shown below).

-

Halsey plaques (near the altar). Refer to the Halsey family page for more details on the individuals.

-

In the Lady Chapel, a plaque and window dedicated to Major William Armstrong. He and his family lived in the Manor House from 1879.

-

A plaque to George Dawson (refer section on Curates below), who was curate 1705-1755. The Latin inscription translates drily as “Contented with his lot, but relying on the hope of a better one”.

-

A plaque to the Cawthorn family, including Mary Cawthorn, who can claim to be Pirbright’s first historian.

-

A plaque to the Stirling family. They lived in Pirbright Lodge after Admiral Byron, but probably made their money by selling textiles to slave traders in the Caribbean.

The Churchyard

The churchyard is one of the most peaceful places in all of Pirbright. In recent years the grounds have been kept very well, and unwelcome weeds kept at bay. It is one of our favourite places in the entire village.

In this section, we will first mention a few items that can be seen on the outside of the church building itself, as well as the lych gate. We will then mention some of the more notable gravestones, with references to the individuals beneath them. The reader may need to search a little to find all of them!

The outside of the church contains some interesting features:

-

The tower and the basal stones of the walls of the church are blocks of Heath Stone (or Pirbright Stone). This is a hard, fine sandstone found locally and quarried in earlier years for building material. We do not think that any natural outcrops of the stone exist any more.

-

As described above, the current building was built in 1785. Most, if not all of, these blocks of Heath Stone would have been reused from the earlier building on the site.

-

In the mortar between the stones of the tower, an excellent display of galleting can be clearly seen. This process involved the insertion of small pebbles into the wet mortar at regular intervals, almost certainly for decorative purposes. We think that the darker pebbles in Pirbright church are made from Carstone, a hard band of dark, iron-rich rock which occurs as layers within the lighter-coloured Heath Stone. Galleting can be found in some other churches in south-east England and Norfolk. An example of the galleting on the church tower is shown left (alongside a set of initials – refer point below).

-

If one looks at the tower stonework carefully, several initials can be seen. These are “Masons’ marks”, ie the initials of the masons who built the tower, sometimes with the date appended. In the case of these particular marks, some of the churchwardens appear to have joined in the fun and added their initials.

-

There are more masons’ marks on the brickwork further along the outside of the church. We have shown samples below. There are several other sets of initial ending in a W. Perhaps these were relatives of Thomas Woods, the churchwarden?

If we turn our attention to the churchyard itself, we can see, very near the masons’ marks on the brickwork, 2 headstones of interest:

-

The headstone of the same Thomas Woods (the churchwarden, who died in 1822) lies very close to this spot.

-

Another nearby headstone is that of George Martin of Bullswater Farm, who died in 1759. His is probably the oldest legible headstone in the churchyard.

Moving further from the church down the central path, we can find a plot of Halsey gravestones. The earliest Halseys were buried in the Mortuary Chapel inside the church (refer above), but from c1877 members of the Halsey family were buried in this plot. Stones for Henry Halsey 2 and his wife Caroline can be readily seen – Henry’s is one of the largest stones in the whole churchyard. The stones of Edward Joseph Halsey (1836-1905) and his wife, Katherine are also easy to find. Edward Joseph Halsey (the third son of Henry Halsey 2) lived a life of philanthropy and service to the community, and was much loved.

Also easy to spot are the absences of any stones for Henry Halsey 3 and Henry Halsey 4 – both regarded as the “black sheep” of the family.

As we continue along the path eastwards, after a little while we can see the tomb for Commander Basil Guy VC – a flat stone lying close to the path on the left, but easy to miss. We have mentioned Commander Guy a couple of times above.

And then, a little further along the path is the monolith to Sir Henry Morton Stanley, which is absolutely impossible to miss. Unquestionably one of the Top 10 sights of Pirbright (assuming such a list has been compiled), it is a thing of awe. The stone itself was brought to Pirbright from Frenchbeer Farm on Dartmoor, and is inscribed in a forceful, no-nonsense script. The phrase “Bula Matari” means “Breaker of rocks” in the KiKongo language, and apparently refers to Stanley introducing the sledgehammer to the Congolese.

Stanley had an extraordinary life, which is spelt out in the section dealing with Furzehill, where he lived from 1893 to his death on 1904. His meeting with David Livingstone in 1871 is the stuff of legend. Much less well-known is his possible connection with 2 other Pirbright residents with African connections. These are also described in the Furzehill section.

When Stanley died in 1904, the first part of the burial service was held in Westminster Abbey, followed by a journey on the Necropolis Railway to Brookwood, and a much shorter service in Pirbright. The monolith itself is much-photographed, so we have shown instead 2 rarities below. On the left is a picture-postcard from c1910, showing Stanley’s grave at that time. The colouring of the postcard is decidedly odd, and we disown any responsibility for it. And on the right is a 1973 first-day cover of 2 stamps depicting Livingstone and Stanley, addressed to Richard Morton Stanley, Sir Henry’s grandson, at Furzehill Place.

Further on, at the far end of the churchyard is the oak Calvary, dedicated to those from Pirbright who fell in the 2 World Wars. A photo of the Calvary on a winter’s day in 2010 is shown right.

Perhaps the reader may now retrace their steps towards the lych gate near the church at the entrance from the road. It was built in 1907, and the stonework contains more highly visible galleting. Below on the left is a picture of the old gate. The photo on the right shows the new gate under construction, probably by John Faggetter, as two of his sons are pictured.

A little further past the lych gate, an example of a railed tomb can be seen. This dates from 1857 and is the grave of Richard Chasmore of Pullens Farm, who died in 1857. The railings no longer exist, but their marks on the basal stone are clearly visible. Why were some tombs railed in the 19th century? Simple – to deter graverobbers… We have shown below a recent photo of the tomb, as well as an earlier photo, when the railings were intact.

Incumbents

We can do no better than reproduce below (with many thanks) a list of incumbents prepared by James Grimshaw for his 2018 booklet. James has added some very helpful notes against many of the names. We have added some further comments below the list.

We have written about many of these people elsewhere on this site, in the sections dealing with their houses. But a few specific mentions are made below.

George Dawson (1705-1755) had a long spell (50 years) as curate. He was much loved by parishioners, and is rumoured to be buried beneath the chancel. He has his own plaque in the church. The latin text on the plaque translates as “Contented with his lot, but relying on the hope of a better one”.

Arthur Krauss (1898-1924) managed to upset the local parishioners several times early on in his curacy. His grandfather had emigrated from Germany to Manchester, where Arthur was born. Shortly after arriving in Pirbright, he stopped the childrens’ annual Christmas treat, because certain permissions had not been sought by the sponsor, Lord Pirbright. This created a furore, which was reported in national newspapers with the headline “Vicar censured by his flock”.

A few months later, when Lord Pirbright had built the village hall, Krauss refused to ring the church bells at the opening ceremony (attended by one of Queen Victoria’s daughters). In protest at this, the bell-ringers refused to ring on Sundays for some time.

Finally, on Lord Pirbright’s death in 1903, Krauss locked the bell chamber and left the village, to frustrate any attempt to toll the bells. This caused something of a riot, and police had to be called in to restore order. Most unusual goings-on for Pirbright!

Things later smoothed over with his parishioners. During WW1 Arthur understandably changed his German-sounding name to Nield – his mother’s maiden name. To the right is a photo of Arthur.

We’ll leave you with 2 of our favourite pictures of the church.